Whether you own a TV or radio, read a newspaper, or get your news online, it’s a fairly safe bet that the bulk of the economic news you are receiving at the moment sounds fairly gloomy.

Even if we could ignore the news, which is often more noisy than informative, we can’t easily ignore that the price of food, petrol and many other essential goods have been rising sharply in recent months, putting pressure on household budgets.

This comes at a time when New Zealand house prices also seem to have peaked. After having accelerated strongly throughout much of 2021, helping homeowners at least ‘feel’ wealthier, housing market indicators now suggest prices could be easing in many regions. And, while the housing market begins to cool, mortgage rates are heading in the other direction (higher), which will only serve to crimp discretionary spending even further.

As spending reduces across the economy, and without our border and immigration policies currently enabling enough visiting holidaymakers or migrant workers to take up the slack, the immediate economic outlook appears weaker than the post-covid global reopening world that many envisaged was awaiting us this year.

While New Zealand’s official unemployment rate is at record lows, and our exporters continue to perform fairly well supplying a world still scrambling to satisfy widespread food and commodity shortages, these appear to be isolated rays of sunshine peeking out from behind a thickening bank of economic cloud.

Consumers and businesses have shown great resilience over the last few years. But the economic environment continues to be challenging and the pathway towards a sustainable economic recovery (perhaps with an initial period of low or negative growth), is unlikely to be smooth.

Inflation pressures

One of the elements that will have a bearing on the shape and speed of the recovery will be what happens with inflation.

The roots of the current surge in global inflation can be traced all the way back to the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, when a large imbalance between the supply and demand for goods emerged.

The global economy contracted sharply in the first half of 2020 as lockdowns were imposed, but what followed was a highly unusual recession as households were largely shielded from economic pain. Many were able to continue to work from home on full pay, while others had their balance sheets protected by various government payments and employment subsidies such that, in aggregate, net savings rose sharply.

With consumers relatively flush with cash and most parts of the global economy still closed, notably the services sector, this pent-up demand was directed into the goods sector and, in New Zealand’s case, the housing market.

While the supply of goods can often struggle to keep pace with demand shocks even in normal economic times, strains on production were amplified by Covid lockdowns and the simultaneous disruption to global supply chains. Shortages of goods caused supplier delivery times to lengthen, and the deteriorating imbalance between supply and demand flowed through to consumers in the form of higher prices.

More recently, the spill-over from the tragic events in Ukraine has only exacerbated these underlying inflation trends as commodity prices have soared, lifting inflation even further.

However, inflation has begun to show some tentative signs of softening, even if the official (backward looking) figures still look strong. Global shipping rates spiked during the pandemic due to supply chain constraints, and the higher freight costs were typically passed on to consumers. However, the Freightos Baltic Index (FBX) Global Container Index suggests these are now well off their highs, having fallen to around US$6,500 per container, compared with around US$11,000 per container in late 2021. It is a tangible sign that some of the recent freight congestion is finally starting to ease.

Similarly, higher oil prices have been hurting consumers at the petrol pump with the international oil price rising from around US$50 per barrel in February 2020 to around US$120 per barrel by early June 2022. However, in the last few weeks the oil price has moved steadily downwards to hover around the US$100 per barrel level. Price declines have also been seen in some other key industrial commodities such as copper, which is used in building construction and electronic product manufacturing. After more than doubling in price from March 2020 to the end of February 2022, the copper price has eased over 20% since.

All of these more recent price trends help reinforce the idea that inflation, whilst continuing to be problematic now, may begin to ease over the remainder of 2022.

Economic growth

As central banks have been steadily revising their inflation expectations upwards, these have been accompanied by downward revisions in projections for global GDP growth.

The recent World Bank Global Economic Prospects Report highlighted this only too clearly.

In January, it forecast global growth for 2022 of 4.1%, but barely six months later, in its June update, this was cut sharply to 2.9%, a nearly one-third reduction from its earlier estimate.

Economic activity has so far been relatively robust as consumers have shown an ability to absorb higher prices, in part due to running down the savings they accumulated during the initial phase of the pandemic. The subsequent tight labour market and pick-up in wage growth has also helped. While these factors should remain supportive for a time, some cracks have begun to emerge on the demand side of the global economy.

With inflation outstripping wage growth in most countries, a squeeze on real incomes has started to erode consumer confidence. Some measures of consumer confidence in the US and UK have fallen to levels not seen since the global financial crisis, while confidence is declining in Europe. It’s the same in New Zealand with the ‘cost of living crisis’ now widely recognised as the number one issue facing households.

All of this suggests that consumers may soon be less willing (or able) to tolerate higher prices in the future, and there is even a risk of outright declines in demand. In the case of recent oil, copper and other commodity price declines, this adjustment may already be underway.

Meanwhile, now that central banks are finally getting on with the job of raising interest rates and global bond markets price in additional rate hikes, there are also signs that tighter financial conditions are starting to have an impact.

In the US, 30-year mortgage rates have climbed to 5.7% in mid-June, the highest level since 2008, and this has coincided with a deterioration in US housing market.

The New Zealand housing market is also showing clear signs of having cooled from the FOMO (fear of missing out) days of late 2021/early 2022. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand was amongst the first of the global central banks to begin raising interest rates late last year, and with floating mortgage rates now nudging 5.5%, we are seeing more regular commentary suggesting a

slowdown in house sales. In some regions, house prices may already be easing.

All of this makes for a very difficult environment for policymakers. Faced with widespread pricing pressures, central banks have determined that tackling inflation is their highest priority, and higher interest rates are the primary tool at their disposal to achieve it. Therefore, as long as inflation remains a concern, central banks will likely continue raising interest rates while maintaining cautionary forward guidance, in an effort to cool activity.

Bear markets

As if this escalating inflation and weakening economic growth environment wasn’t enough, the ongoing war in the Ukraine and the drawn-out global impact of Covid, are other factors continuing to create uncertainty or unease in the minds of many investors.

In general, when investors are feeling happy and confident, they are often more comfortable allocating to higher risk investments. However, when they are lacking in confidence, they are less inclined to take higher risks. Market commentators have a specific phrase for this general investor attitude, they refer to it as ‘investor sentiment’, either positive or negative.

Recently, investor sentiment has been more consistently negative. And it is with this backdrop that global share markets have been struggling over recent months.

On 14 June, the main New Zealand share market (the S&P/NZX 50 Total Return Index) slipped into official ‘bear market’ territory. A bear market is generally defined as a decline of at least -20% from the prior market peak, which in New Zealand’s case was on 4 October 2021. At time of writing, the S&P/NZX 50 had since rallied a little, reducing the size of this decline, but nevertheless it reflects a very tough period for local share market investors.

This is not an issue unique to New Zealand. The globally significant US share market has had it even worse. The headline S&P 500 Index similarly fell into bear market territory on 13 June, while experiencing its worst first half of the year since 1970. The other high profile US index, the Nasdaq 100 which includes all the large technology companies, ended June over -30% below its peak of 27 December 2021.

These returns are reflective of markets that are facing a range of uncertainties and they are therefore pricing in a high degree of caution or pessimism. But that doesn’t mean that the returns outlook for the months ahead is necessarily poor.

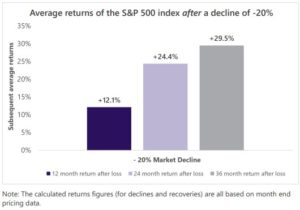

When we review historical data (back to 1940) using the leading US share market index as our reference (the S&P 500 index), the chart below summarises the average one, two and three year performance of the S&P 500 after all previous bear market declines of -20%.

As the chart clearly shows, the average return after a decline of -20% is positive in all analysed time periods, and strongly positive over the subsequent two and three year periods. As challenging as things may seem now, this is a timely reminder that markets are always much more focused on where the economy is going, and not where it has been. After all, share markets are a leading indicator for the economy.

Bond markets have also experienced a poor start to the year, with interest rates in many countries having increased and with further rate rises projected. It is a unique aspect of bond pricing that when interest rates rise, two things happen –

- The prices of existing bonds go down (which happens immediately)

- The expected future returns of those existing bonds go up (with these higher returns being delivered over time)

In this regard, falling bond prices are felt immediately in portfolio valuations, while the higher expected future returns are only received in the months that follow. One small comfort from this is that with current bond yields now much higher than they have been for several years, the expected future returns from bonds are looking increasingly attractive.

This too will pass

Even if New Zealand or any other countries enter a technical recession this year (two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth), recessions don’t tend to last for very long and don’t necessarily impact asset prices. As we have already noted, if demand and inflation show more obvious signs of reducing, central bank policies can also be expected to eventually pivot from fighting inflation to supporting growth.

For now, uncertainties are elevated and these uncertainties have been fully priced into markets. While this has been a big factor in the poor share market returns year to date, it doesn’t tell us anything about the returns we should expect for the remainder of this year.

Markets are relentlessly forward-looking. They don’t only calibrate the information that is known today, they also calibrate all the fears, hopes and expectations of every market participant. Whilst investor sentiment has been very negative, and this has weighed heavily on market prices, we know that sentiment and markets can turn very quickly. Just as the prospect of better economic times ahead can be a catalyst that can help move markets higher, and it can happen well before the benefits are readily observable in the economy around us.

Given the current low market starting point, if sentiment was to begin to improve in the coming weeks and months around any one or more of the current uncertainties (inflation, central bank policy, economic growth, Covid or the Ukraine conflict), then share markets at these lower prices might suddenly look a lot more appealing.

As always, in periods like this where the market has been challenging, it is best not to try and ‘time’ your exposure. Whilst it might be tempting to think that you could just sit out of the markets and wait for the current storm to blow over, the forward-looking markets will always go up, and sometimes strongly, well before the economic clouds have cleared. And given the speed that markets can react, being on the sidelines and missing the recovery can often be far more detrimental to a long term plan, than absorbing the current lower valuations and higher volatility of returns.

The most reliable advice is always to maintain the risk exposure that you set, and considered appropriate, when the skies were clearer. Investing more when prices are cheaper is usually an even better option, but that may not be an option that is available to everybody. If it isn’t, just batten down the hatches and wait this one out. The skies always clear and the markets always recover. We just don’t ever quite know the timing.