The fourth quarter of 2021 rounded out another year when developed share markets posted strong returns, despite ongoing uncertainties relating to global supply chains, inflation, interest rates and, of course, emerging variants of Covid-19.

Market performance continued to be driven more by supportive economic and financial data such as positive economic growth, low interest rates, and good corporate earnings.

While many uncertainties remain, we need to remember that all current information, even in matters where the outcome is uncertain, is already factored into prevailing market prices.

This attribute of market pricing is always useful to keep in mind because it helps explain the apparent paradox of how markets can still go up when bad news is announced. It can often occur when the market was expecting something even worse to happen! If the confirmed bad news turns out to be better than the news the market had priced in, then prices will often have room to adjust upwards.

It also provides some explanation for how markets have behaved as new Covid variants have emerged. While the late 2021 rise of Omicron seemed to cast renewed uncertainty over the outlook for 2022 (in much the same way Delta did a year earlier), the markets overall were relatively unaffected.

This suggests the markets did not view the threat of Omicron to be anything out-of-the-ordinary; at least not when compared to our experience over the prior 21 months.

2021 recap

Following a quite extraordinary year in 2020, which saw the unwelcome arrival of Covid-19, 2021 was a year of transition mixed with hope for a return to normalcy. It was also a year that showed,

yet again, the difficulty of making investment decisions based on predictions of where markets will go.

Coming out of a volatile 2020, investors sought signals as to which way the global economy was headed. The distribution of vaccines and the easing of lockdowns helped foster an economic rebound, but the emergence of new Covid variants was a constant reminder that we weren’t in a post-Covid world just yet.

Despite these challenges, global gross domestic product grew strongly, completing the transition from recovery to expansion and eventually surpassing its pre-pandemic peak.

While at the nadir of the crisis in 2020, high unemployment looked set to be a long-term issue. However, as the economic recovery progressed in 2021 it was increasingly accompanied by labour shortages, supply chain issues, and fears of rising inflation.

Prices increased rapidly in essential areas such as food and energy, and the media was filled with speculation about where inflation would go, what was causing it, how long it might last, and what could, or should, be done in response.

Supply chain update

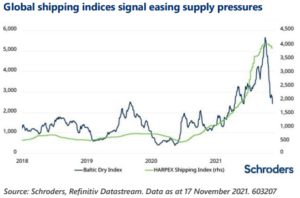

It’s too early to be definitive, but the significant supply chain disruptions in 2021, largely linked to Covid-19-related production constraints and transportation bottlenecks, may already have peaked. Although, if true, it may still take some time for this to eventually filter through to the prices we pay for many goods and services.

Supply chain backlogs historically adjust quite rapidly after periods of stress, as the market responds to higher demand and rebuilds inventory.

Whilst the Covid-induced shutdown contributed to a global supply chain fracture of a magnitude rarely seen outside of a major global war, the recent indications from global shipping indices are that the seeds of a recovery may be underway.

The chart below shows recent declines in both the Baltic Dry Index (dry bulk freight costs) and in the HARPEX Shipping Index (weekly container shipping rates).

This is a positive sign that supply chain disruptions could be slowly abating and freight-related pricing pressures might begin to slowly ease.

Energy Prices

While the below shipping data looks encouraging, the same cannot be said for energy prices.

The global economic recovery is boosting demand for oil and gas at a time when supply growth is static. While governments have been encouraging energy companies to spend more money on renewable energy sources, this has often come at the expense of spending on traditional energy exploration and production. And, while renewables may be the longterm future, for the immediate future it is still oil and gas that powers much of the world.

This relative underinvestment on traditional energy sources means existing supplies are not only tight, but in many cases set to shrink further, particularly if reduced emissions targets are to be met. Until such time as a significant transition to renewable energy sources can be achieved, traditional energy prices look likely to stay elevated.

Rising geopolitical tensions

As the year drew to a close there was considerable speculation that Russia could be planning an invasion of the Ukraine in early 2022 as tens of thousands of Russian troops were observed near the Ukranian border.

The roots of conflict between Russia and Ukraine have a history that dates all the way back to the Middle Ages but, at its heart, it boils down to Moscow’s unwillingness to accept Ukraine’s independence.

The annexation of Crimea from the Ukraine in March 2014 marked a recent turning point in relations and the beginning of what some now refer to as an ‘undeclared war’ between the two countries.

On the diplomatic stage, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman began negotiations on 10 January with her Russian counterpart Sergei Ryabkov, over Russia’s military buildup and on Moscow’s security demands from Western countries.

Disappointingly, and not at all surprisingly, even before this meeting began both sides had publicly dismissed expectations of a breakthrough.

NZ residential property

A report from independent real estate consultancy firm Knight Frank highlighted New Zealand’s residential real estate prices led the world over the last five years (up 60%), although slipping to third on the index this year.

Some of the contributing factors behind this strong performance are widely acknowledged:

• New Zealanders have historically been highly enthusiastic property investors.

• New Zealand has enjoyed strong positive net migration (up to March 2021).

• There is a relative scarcity of housing stock currently available.

• The recent availability of extremely low mortgage interest rates.

• Housing has been seen as an appealing investment option for many Kiwi’s unexpectedly grounded due to Covid lockdowns.

However, with interest rates in New Zealand now on the rise and pipeline building consents much higher, there are reasons to think the pace of the recent price rises could ease in 2022.

This is particularly so with net migration remaining static due to closed international borders. In the year to March 2021, the New Zealand population increased by 91,680 due to strong net migration, while in the following 12 months this figure understandably slumped to just 3,229.

It is unclear what migration trends we should expect when New Zealand’s borders do finally reopen. While a return to pre-Covid migration rates is unlikely, some commentators are speculating that New Zealand could even see a net population outflow as displaced or disgruntled workers chase better employment opportunities offshore. Alternatively, New Zealand’s low infection and mortality rates throughout the pandemic have not gone unnoticed on the world stage, so it’s equally possible that our net migration rates could be boosted by a surge in ‘safe haven’ demand.

China lowers lending ratio In December, in a move designed to support their ailing real estate market along with the broader Chinese economy, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) reduced the level of capital required to be held by domestic banks by 0.5 percentage points.

This followed a similar cut in July and came as several of the largest property developers in China had begun defaulting on their debt. By requiring Chinese banks to hold a lower proportion of deposits on reserve, the PBOC is effectively encouraging local banks to lend more money to businesses and consumers.

This is being interpreted as a sign of concern from the Chinese authorities about the current weakness in the Chinese property market, which accounts for about a quarter of China’s economic activity.

It also marks an interesting contrast in approach to western central banks such as the Bank of England or the US Federal Reserve, which are both looking to tighten, not relax, their monetary conditions.

A return to conventional monetary policy?

In 2020, aiming to defy a potentially devastating economic outcome from Covid-19, global central banks quickly provided unprecedented levels of financial support to markets. Almost two years later, albeit with a very hefty price tag, this strategy seems to have achieved its goal.

Apart from an initial slump in Feb/Mar 2020, markets have continued to function effectively. Many companies were able to survive or even thrive in the intervening months, and unemployment levels in key developed markets are now significantly lower than most 2020 projections.

Now however, with global economic growth indicators remaining positive and inflation spiking around much of the world (even if only temporarily), central bankers are reviewing the extent to which this significant financial stimulus may still be required. The higher inflation rates alone are an indicator that the patient is ‘responding to the medication’, and that perhaps they can begin to look to reduce the dosage.

In fact, given the wording of many central bank monetary policy target agreements which are specifically aimed at controlling inflation within specific parameters, the existing levels of financial stimulus are likely to become harder and harder to maintain.

As quantitative easing programmes gradually begin to wind down and the world takes a collective step back towards a more conventional monetary policy approach, this creates another uncertainty. After years of abnormally accommodative policy settings, weaning the patient off this stimulatory financial medication entirely is unlikely to be a smooth transition.

What lies ahead?

We could offer you our best guess, but if we did you should be skeptical.

In spite of interpreting some of the information currently available in the markets in an effort to provide a broader context, there is sadly no reliable link between this information and future market performance, especially in the short term. Thankfully, it’s not a problem we grapple with alone.

In truth, all investors, including all professional investors, suffer from the same problem. We just don’t know, and can’t know with certainty, what the future holds.

Over a long term horizon, shares will always have greater performance potential than bonds, and this continues to hold true today even though share markets have generally been performing very well for a long time. With interest rates still at relatively low levels in developed markets, overall return expectations from all fixed interest assets remains more subdued, at least for the time being.

However, given the much higher risk (variation in returns) that accompanies share market investments, investors with a high exposure to shares will inevitably need to navigate a fairly bumpy path. To balance out the bumps, maintaining a diversified portfolio of risk premia, including an appropriate mixture (for you) of higher risk and lower risk assets, will almost always be the best approach.

The mistake a lot of individual investors make on their own account is they will often unwittingly end up taking investment risks not well suited to their needs. Chasing returns is one thing; managing risk is something else entirely. Knitting these two together is where good advice and a prudent investment plan sit.

And, as all great advisers know, optimising your investments isn’t just a mechanical discussion about risk and return, it’s about creating and managing a portfolio of assets that can allow you to achieve your goals without interfering with the rest of your life.