By Carl Richards

Because I live in the mountains where the weather changes often, I’ve never really relied on forecasts. Instead, I prefer to look out of the window to see what’s happening in real-time. My low-tech approach made sense for years. But my strategy—and the jokes about weather forecasters—may one day be a thing of the past.

Even as you yell at your TV during the weather segment of your local newscast, forecasts are actually getting more accurate. Three-day forecasts today are as good as 36-hour forecasts were in the 1980s, and the average error in hurricane-tracking predictions has been slashed by two-thirds since the early 1970s.

This improvement is a result of computer models that collect all the data—temperatures, clouds, and winds—and put it into mathematical equations. These models were built by looking for and identifying variables that offered some predictive value. Over time, as more of these factors were identified and fed into the model, the accuracy of the forecast improved.

We have been attempting to do the same thing with the stock market. We have spent endless amounts of time, money, and human capital trying to identify variables that help predict market behavior. We have looked at the ridiculous (Super Bowl winners) and the more serious (past performance). Still, none of them have much predictive value, particularly over the short term.

But that doesn’t stop us from looking, which often leads to guessing. And guessing is no way to make investment decisions.

The pioneering investor Ben Graham is said to have described the market as being hard to predict: “In the short run, the stock market behaves like a voting machine, but in the long term, it acts like a weighing machine.”

And because humans are doing the voting, it’s very difficult to predict which way the vote will go. Another reason is that investing is not a physical science.

It’s not like gravity or even the weather. It doesn’t follow set laws. On any given day, the stock market represents the collective feelings of all of us. More often than not, those feelings are based on fear or greed. And it is only in hindsight that we recognize our mistakes.

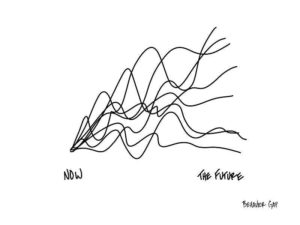

So while on one level, human behavior seems predictable (e.g., we get excited and buy stocks when they are flying high; we get scared and sell when stocks decline), it’s awfully hard to know what we’re doing until it’s too late.

I bring up the subject of forecasting because, despite knowing better, I still see a lot of people playing what I consider a fool’s game. There is no proven, market-predicting model hidden in a computer that only a few people have access to.

The facts have remained the same. Over time (think 10, 15, or 20 years), stocks typically do better than bonds, and bonds typically do better than cash. Low expenses are typically a good sign of future relative performance. We also know that a diversified portfolio will help protect you from the variability of the stock market.

Beyond that, it’s just a guessing game, and we’re pretending to know something we don’t.

I’m ready to stop pretending. Are you?

-Carl

Carl Richards is the founder of the Behaviour Gap and the Sktech Guy from the NY Times. You can visit his website, www.behaviourgap.com